Luciferase is a generic term for the class of oxidative enzymes used in bioluminescence and is distinct from a photoprotein. The name is derived from Lucifer, the root of which means 'light-bearer' (lucem ferre). One example is the firefly luciferase (EC 1.13.12.7) from the firefly Photinus pyralis. "Firefly luciferase" as a laboratory reagent often refers to P. pyralis luciferase although recombinant luciferases from several other species of fireflies are also commercially available.

Examples

A variety of organisms regulate their light production using different luciferases in a variety of light-emitting reactions. The most famous are the fireflies, although the enzyme exists in organisms as different as the Jack-O-Lantern mushroom (Omphalotus olearius) and many marine creatures.

Firefly and click beetle

The luciferases of fireflies - of which there are over 2000 species - and of the Elateroidea (fireflies, click beetles and relatives) in general - are diverse enough to be useful in molecular phylogeny. In fireflies, the oxygen required is supplied through a tube in the abdomen called the abdominal trachea. One well-studied luciferase is that of the Photinini firefly Photinus pyralis, which has an optimum pH of 7.8.

Sea pansy

Also well studied is the fancy sea pansy, Renilla reniformis. In this organism, the luciferase (Renilla-luciferin 2-monooxygenase) is closely associated with a luciferin-binding protein as well as a green fluorescent protein (GFP). Calcium triggers release of the luciferin (coelenterazine) from the luciferin binding protein. The substrate is then available for oxidation by the luciferase, where it is degraded to coelenteramide with a resultant release of energy. In the absence of GFP, this energy would be released as a photon of blue light (peak emission wavelength 482Â nm). However, due to the closely associated GFP, the energy released by the luciferase is instead coupled through resonance energy transfer to the fluorophore of the GFP, and is subsequently released as a photon of green light (peak emission wavelength 510Â nm). The catalyzed reaction is:

- coelenterazine + O2 â†' coelenteramide + CO2 + photon of light

Bacterial

Bacterial bioluminescence is seen in Photobacterium species, Vibrio fischeri, haweyi, and harveyi. Light emission in some bioluminescent bacteria utilizes 'antenna' such as 'lumazine protein' to accept the energy from the primary excited state on the luciferase, resulting in an excited lulnazine chromophore which emits light that is of a shorter wavelength (more blue), while in others use a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) with FMN as the chromophore and emits light that is red-shifted relative to that from luciferase.

Dinoflagellate

Dinoflagellate luciferase is a multi-domain protein, consisting of an N-terminal domain, and three catalytic domains, each of which preceded by a helical bundle domain. The structure of the dinoflagellate luciferase catalytic domain has been solved. The core part of the domain is a 10 stranded beta barrel that is structurally similar to lipocalins and FABP. The N-terminal domain is conserved between dinoflagellate luciferase and luciferin binding proteins (LBPs). It has been suggested that this region may mediate an interaction between LBP and luciferase or their association with the vacuolar membrane. The helical bundle domain has a three helix bundle structure that holds four important histidines that are thought to play a role in the pH regulation of the enzyme. There is a large pocket in the β-barrel of the dinoflagellate luciferase at pH 8 to accommodate the tetrapyrrole substrate but there is no opening to allow the substrate to enter. Therefore, a significant conformational change must occur to provide access and space for a ligand in the active site and the source for this change is through the four N-terminal histidine residues. At pH 8, it can be seen that the unprotonated histidine residues are involved in a network of hydrogen bonds at the interface of the helices in the bundle that block substrate access to the active site and disruption of this interaction by protonation (at pH 6.3) or by replacement of the histidine residues by alanine causes a large molecular motion of the bundle, separating the helices by 11Å and opening the catalytic site. Logically, the histidine residues cannot be replaced by alanine in nature but this experimental replacement further confirms that the larger histidine residues block the active site. Additionally, three Gly-Gly sequences, one in the N-terminal helix and two in the helix-loop-helix motif, could serve as hinges about which the chains rotate in order to further open the pathway to the catalytic site and enlarge the active site.

A dinoflagellate luciferase is capable of emitting light due to its interaction with its substrate (luciferin) and the luciferin-binding protein (LBP) in the scintillon organelle found in dinoflagellates. The luciferase acts in accordance with luciferin and LBP in order to emit light but each component functions at a different pH. Luciferase and its domains are not active at pH 8 but they are extremely active at the optimum pH of 6.3 whereas LBP binds luciferin at pH 8 and releases it at pH 6.3. Consequently, luciferin is only released to react with an active luciferase when the scintillon is acidified to pH 6.3. Therefore, in order to lower the pH, voltage-gated channels in the scintillon membrane are opened to allow the entry of protons from a vacuole possessing an action potential produced from a mechanical stimulation. Hence, it can be seen that the action potential in the vacuolar membrane leads to acidification and this in turn allows the luciferin to be released to react with luciferase in the scintillon, producing a flash of blue light.

Copepod

Newer luciferases have recently been identified that, unlike other luciferases above, are naturally secreted molecules. One such example is the Metridia luciferase (MetLuc) that is derived from the marine copepod Metridia longa. The Metridia longa secreted luciferase gene encodes a 24 kDa protein containing an N-terminal secretory signal peptide of 17 amino acid residues. The sensitivity and high signal intensity of this luciferase molecule proves advantageous in many reporter studies. Some of the benefits of using a secreted reporter molecule like MetLuc is its no-lysis protocol that allows one to be able to conduct live cell assays and multiple assays on the same cell.

Mechanism of reaction

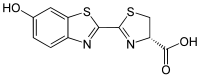

The chemical reaction catalyzed by firefly luciferase takes place in two steps:

- luciferin + ATP â†' luciferyl adenylate + PPi

- luciferyl adenylate + O2 â†' oxyluciferin + AMP + light

Light is emitted because the reaction forms oxyluciferin in an electronically excited state. The reaction releases a photon of light as oxyluciferin returns to the ground state.

Luciferyl adenylate can additionally participate in a side reaction with O2 to form hydrogen peroxide and dehydroluciferyl-AMP. About 20% of the luciferyl adenylate intermediate is oxidized in this pathway.

The reaction catalyzed by bacterial luciferase is also an oxidative process:

- FMNH2 + O2 + RCHO â†' FMN + RCOOH + H2O + light

In the reaction, a reduced flavin mononucleotide oxidizes a long-chain aliphatic aldehyde to an aliphatic carboxylic acid. The reaction forms an excited hydroxyflavin intermediate, which is dehydrated to the product FMN to emit blue-green light.

Nearly all of the energy input into the reaction is transformed into light. The reaction is 80% to 90% efficient. As a comparison, the incandescent light bulb only converts about 10% of its energy into light. and a 150 lumen per Watt (lm/W) LED converts 20% of input energy to visible light.

Firefly luciferase generates light from luciferin in a multistep process. First, D-luciferin is adenylated by MgATP to form luciferyl adenylate and pyrophosphate. After activation by ATP, luciferyl adenylate is oxidized by molecular oxygen to form a dioxetanone ring. A decarboxylation reaction forms an excited state of oxyluciferin, which tautomerizes between the keto-enol form. The reaction finally emits light as oxyluciferin returns to the ground state.

Bifunctionality

Luciferase can function in two different pathways: a bioluminescence pathway and a CoA-ligase pathway. In both pathways, luciferase initially catalyzes an adenylation reaction with MgATP. However, in the CoA-ligase pathway, CoA can displace AMP to form luciferyl CoA.

Fatty acyl-CoA synthetase similarly activates fatty acids with ATP, followed by displacement of AMP with CoA. Because of their similar activities, luciferase is able to replace fatty acyl-CoA synthetase and convert long-chain fatty acids into fatty-acyl CoA for beta oxidation.

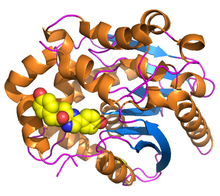

Structure

The protein structure of firefly luciferase consists of two compact domains: the N-terminal domain and the C-terminal domain. The N-terminal domain is composed of two β-sheets in an αβαβα structure and a β barrel. The two β-sheets stack on top of each other, with the β-barrel covering the end of the sheets.

The C-terminal domain is connected to the N-terminal domain by a flexible hinge, which can separate the two domains. The amino acid sequences on the surface of the two domains facing each other are conserved in bacterial and firefly luciferase, thereby strongly suggesting that the active site is located in the cleft between the domains.

During a reaction, luciferase has a conformational change and goes into a “closed†form with the two domains coming together to enclose the substrate. This ensures that water is excluded from the reaction and does not hydrolyze ATP or the electronically excited product.

Spectral differences in bioluminescence

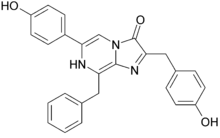

Firefly luciferase bioluminescence color can vary between yellow-green (λmax = 550 nm) to red (λmax = 620). There are currently several different mechanisms describing how the structure of luciferase affects the emission spectrum of the photon and effectively the color of light emitted.

One mechanism proposes that the color of the emitted light depends on whether the product is in the keto or enol form. The mechanism suggests that red light is emitted from the keto form of oxyluciferin, while green light is emitted from the enol form of oxyluciferin. However, 5,5-dimethyloxyluciferin emits green light even though it is constricted to the keto form because it cannot tautomerize.

Another mechanism proposes that twisting the angle between benzothiazole and thiazole rings in oxyluciferin determines the color of bioluminescence. This explanation proposes that a planar form with an angle of 0° between the two rings corresponds to a higher energy state and emits a higher-energy green light, whereas an angle of 90° puts the structure in a lower energy state and emits a lower-energy red light.

The most recent explanation for the bioluminescence color examines the microenvironment of the excited oxyluciferin. Studies suggest that the interactions between the excited state product and nearby residues can force the oxyluciferin into an even higher energy form, which results in the emission of green light. For example, Arg 218 has electrostatic interactions with other nearby residues, restricting oxyluciferin from tautomerizing to the enol form. Similarly, other results have indicated that the microenvironment of luciferase can force oxyluciferin into a more rigid, high-energy structure, forcing it to emit a high-energy green light.

Regulation

D-luciferin is the substrate for firefly luciferase’s bioluminescence reaction, while L-luciferin is the substrate for luciferyl-CoA synthetase activity. Both reactions are inhibited by the substrate’s enantiomer: L-luciferin and D-luciferin inhibit the bioluminescence pathway and the CoA-ligase pathway, respectively. This shows that luciferase can differentiate between the isomers of the luciferin structure.

L-luciferin is able to emit a weak light even though it is a competitive inhibitor of D-luciferin and the bioluminescence pathway. Light is emitted because the CoA synthesis pathway can be converted to the bioluminescence reaction by hydrolyzing the final product via an esterase back to D-luciferin.

Luciferase activity is additionally inhibited by oxyluciferin and allosterically activated by ATP. When ATP binds to the enzyme’s two allosteric sites, luciferase’s affinity to bind ATP in its active site increases.

Applications

Luciferase can be produced in the lab through genetic engineering for a number of purposes. Luciferase genes can be synthesized and inserted into organisms or transfected into cells. Mice, silkworms, and potatoes are just a few of the organisms that have already been engineered to produce the protein.

In the luciferase reaction, light is emitted when luciferase acts on the appropriate luciferin substrate. Photon emission can be detected by light sensitive apparatus such as a luminometer or modified optical microscopes. This allows observation of biological processes. Since light excitation is not needed for luciferase bioluminescence, there is minimal autofluorescence and therefore virtually background-free fluorescence. Therefore, as little as 0.02pg can still be accurately measured using a standard scintillation counter.

In biological research, luciferase is commonly used as a reporter to assess the transcriptional activity in cells that are transfected with a genetic construct containing the luciferase gene under the control of a promoter of interest. Additionally proluminescent molecules that are converted to luciferin upon activity of a particular enzyme can be used to detect enzyme activity in coupled or two-step luciferase assays. Such substrates have been used to detect caspase activity and cytochrome P450 activity, among others.

Luciferase can also be used to detect the level of cellular ATP in cell viability assays or for kinase activity assays. Luciferase can act as an ATP sensor protein through biotinylation. Biotinylation will immobilize luciferase on the cell-surface by binding to a streptavidin-biotin complex. This allows luciferase to detect the efflux of ATP from the cell and will effectively display the real-time release of ATP through bioluminescence. Luciferase can additionally be made more sensitive for ATP detection by increasing the luminescence intensity by changing certain amino acid residues in the sequence of the protein.

Whole animal imaging (referred to as in vivo or, occasionally, ex vivo imaging) is a powerful technique for studying cell populations in live animals, such as mice. Different types of cells (e.g. bone marrow stem cells, T-cells) can be engineered to express a luciferase allowing their non-invasive visualization inside a live animal using a sensitive charge-couple device camera (CCD camera).This technique has been used to follow tumorigenesis and response of tumors to treatment in animal models. However, environmental factors and therapeutic interferences may cause some discrepancies between tumor burden and bioluminescence intensity in relation to changes in proliferative activity. The intensity of the signal measured by in vivo imaging may depend on various factors, such as D-luciferin absorption through the peritoneum, blood flow, cell membrane permeability, availability of co-factors, intracellular pH and transparency of overlying tissue, in addition to the amount of luciferase.

The Glowing Plant project plans to use bacterial bio-luminescent systems to engineer novelty glowing Arabidopsis thaliana plants. Longer term they hypothesize that maybe such systems could be used to create eco-friendly sustainable light sources.

Luciferase is a heat-sensitive protein that is used in studies on protein denaturation, testing the protective capacities of heat shock proteins. The opportunities for using luciferase continue to expand.

See also

- Firefly

- Luciferin

- Firefly luciferin

- Bioluminescence imaging

- Quorum sensing

- Bioluminescent bacteria

- Mouse models of breast cancer metastasis

References

External links

This article incorporates text from the public domain Pfam and InterPro IPR018804 This article incorporates text from the public domain Pfam and InterPro IPR007959 This article incorporates text from the public domain Pfam and InterPro IPR018475